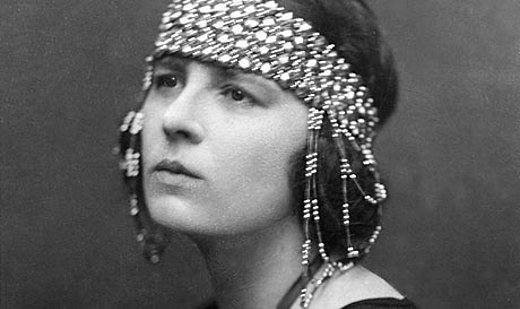

You can interpret it any number of ways but in the end The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is a one-sentence summary kind of book: A bunch of sad-eyed social misfits in a sleepy Southern mill town cluster around the local deaf-mute to pour forth their troubles to an unresponsive, unjudging ear while the deaf-mute (burdened with the ironic name of John Singer) is occupied with confessing his soul to a dear friend of his… who is also a deaf-mute. Yes, it’s that sort of book. Loneliness and isolation are the words of the day. Every man is an island where no plants grow and all fruit falls incommunicably far from the tree. It’s a universe of pessimism, the habitual world of Carson McCullers (1917-1967).

As would be par for the course in her future career, the 23-year-old author took a black comedy premise and played it for full pathos. In 1940 this was the hottest book on the literary market and made her a critical sensation for a few years but, as her physical and mental health ground down, her reputation declined considerably (with the arrival of Flannery O’Connor probably not helping matters). The original ecstatic response to The Heart is a Lonely Hunter, combined with some high-profile booklists and an Oprah endorsement have made it McCullers’ go-to work. Now as I hold the somewhat rare opinion that Reflections in a Golden Eye is her finest work (though won’t be completely sure until I find a copy of The Member of the Wedding), Lonely Hunter appears accomplished yet overstuffed, unforgivably maudlin and twisted at a core level.

Dramatis personae: The unfailingly polite John Singer, above. Biff Bannon, owner of the local drinking establishment, a melancholy man with a special feeling for sick people and cripples and an uneasy attachment to adolescent Mick Kelly. Mick, an awkward misfit girl with musical ambitions who functions as a McCullers’ self-portrait and a reprise of the girl from her debut short story ‘Wunderkind.’ Lastly there are Dr. Copeland, a tubercular black intellectual, and Jake Blount, a mustachioed drunkard. Both want to rally the poor masses and worship at the altar of Karl Marx but are so aggressive in their approaches as to drive off any sympathetic ear, leaving Copeland alienated from his own children and Blount in a state of insanity. All four of these despairing individuals become fixated on Mr. Singer, who’s just too polite to shut his door to them.

McCullers visited time and again in her writings the concept that love can only go one way. In this case everyone obsesses over Mr. Singer, confessing their most private longings to him and seeing in his silence what they need him to feel, but nobody ever tries to interact with him. There is no communication or concern – everyone in the novel is too wrapped up in their own pain to notice anyone else’s. This lonely inability to connect is the loudspeaker theme of the novel and the end of the story is therefore baked in the cake and I am going to freely discuss or drop hints about most of the storylines, though not the denouement of part 2. I also caution you that if you plan to read The Heart is a Lonely Hunter for the engaging plot developments you will most probably be leaving a one-star review on Amazon.

The American Southern Gothic tradition is satisfied right away: this novel is unrelentingly bleak and the gloomy town in all of its decrepitude is splendidly, maddeningly evoked – cold, dirty streets littered with refuse, sick people dying or losing limbs or organs, dying trees, dying cats. And if anyone was going to write a death-world it had to be someone as ill-starred as McCullers, who had already suffered a number of strokes and would be wholly paralysed on her left side by the age of 31. Gothic writers usually give their morbidity a fashionable, theatrical cast but this was never really the case with her and least of all with this novel. Critics of the modern school love to say that she wrote about homosexuals and people of colour but she was writing all the time about sick people. Hers is a world of the terminally ill and this really best explains her characters’ complete inability to achieve companionship or experience even a momentary joy. “Every living thing dies alone,” to quote Donnie Darko. Reading it at the age of 23 (same age as the author was when she wrote it, incidentally) I longed to dismiss it as over-the-top and, although the allegorically bottle-necked setting of Reflections in a Golden Eye was more comfortable to my senses, The Heart is a Lonely Hunter really does a splendid job catapulting a young and healthy reader into the midst of death and decay. All five characters have some kind of rotting albatross around their necks: Biff’s wife, Mick’s sister, Singer’s insane friend Antonopoulos, Blount’s alcoholism, Dr. Copeland’s patients and his own failing lungs. Sickness is everywhere and I’m gonna hand it to her here: the atmosphere is first rate and perfectly sustained from start to finish.

But this underlying motif is not the novel’s primary focus. Death is just a given while loneliness is what McCullers devotes the book to exploring. It starts with Mick Kelly and here my admiration falters. She’s the girl from ‘Wunderkind,’ McCullers’ earliest story, whose pursuit of music proves unattainable – but now padded out to fill a book. Her dreams are childish, her behaviour brattish and her life is made out to be the very stuff of tragedy – as doomed to eternal loneliness as aging, sickening and silenced Dr. Copeland. The job she finally takes at Woolworth’s isn’t just an economic setback and it certainly isn’t depicted as her growing up and shouldering some of the family burden; no, it is the end of all her hopes and dreams, the quashing of that spark of individuality, all over at thirteen. Now no music was in her mind. All of the delicate inference of ‘Wunderkind’ can’t be improved on and that one short story felt far more universal because it had no ambition, it was simply a depiction of wounded adolescence and artistic failure that never tried to be anything more. With Mick, there’s often a cloying and manipulative “poor me” vibe, most noticeable in her attempt to fashion a violin out of a broken ukulele. Why not simply try to repair the ukulele and go from there? Because that wouldn’t be pathetic and doomed enough in its ambitions. The pathos is cheap, at least to my heartstrings. There’s Mozart and then there’s Mantovani. McCullers is going for Mantovani here.

Or take what is arguably the worst scene in the book, which concerns itself with the fate of Baby Wilson, a Shirley Temple lookalike whose chances of leaving town actually look pretty good at the start. Of course you know what’s coming in a book like this. There’s no real surprise here when the 20th Century wears its artistic nihilism on its sleeve. So we are introduced to the local kids straggling around with a loaded gun when Baby comes outside to practice her gymnastic routine. The curse of Chekhov’s Gun came into play immediately: I knew it was going to go off and before Baby even showed up in the scene I knew it would not be hitting one of the whining little street urchins. No, only a cossetted symbol of hope for the future would do and I groaned aloud when – right on cue! – Baby sauntered by all dressed in pink. Again, the pathos was on overload. It was so baldly telegraphed that it flew right past “shocking” or “tragic” and landed on “crass manipulation.”

Again and again the novel bypasses any sense of subtlety without the compensating strength of heartless irony. McCullers plays too heavily upon feelings and I am left with the ungenerous urge to laugh: The fact that Antonapoulos could not read did not prevent Singer from writing to him. He had always known his friend was unable to make out the meaning of words on paper, but as the months went by he began to imagine that perhaps he had been mistaken, that perhaps Antonapoulos only kept his knowledge of letters a secret from everyone. Also, it was possible there might be a deaf-mute at the asylum who could read his letters and then explain them to his friend. He thought of several justifications for his letters, for he always felt a great need to write to his friend when he was bewildered or sad. Once written, however, these letters were never mailed.

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is at its best when looking at the actual interactions among the quintet. There’s not nearly enough of it, as McCullers prefers to keep them in isolation most of the time but it all works remarkably well. Biff tries to get Blount to open up to him but actual interest in his ideas makes the man cagey and guarded. Mick thinks Biff dislikes her when he’s secretly hypnotized. Blount and Dr. Copeland bond over an all-nighter discussing the problems of the country but it all goes straight to hell when they try to share ideas for “the way out. What must be done.” When all four converge on Singer at the same time, McCullers scornfully upends literary convention: Singer was bewildered. Always each of them had so much to say. Yet now that they were together they were silent. When they came in he had expected an outburst of some kind. In a vague way he had expected this to be the end of something. But in the room there was only a feeling of strain.

Biff is the only one who notices the spreading power the mute has over the townspeople and is easily the most observant of the bunch. He’s also the only one who gets to have a really Zen moment. The story ends appropriately with him alone in the night, meditating on human struggle and…valor. He could succumb to terror and despair, he’s as lonely as the next guy, but he pulls himself together and composed himself soberly to await the morning sun. It’s an excellent scene, perhaps the best in the book, and the only one to offer a message that inner strength has any purpose and can actually defeat the crushing nihilism of life that sends people into spirals of empty, abusive, suicidal despair.

Biff is not the most fully realised character, however. Nor is Singer, from whose mind we are deliberately kept at a distance. Instead it is Dr. Copeland. Educated yet wrathful, passive in life yet scornful of God, unable to accept the love of his community, full of fire and regret – all of this makes him an astonishingly real creation and his Christmas Day sermon on Karl Marx is one of the more memorable scenes in the novel. He despises religion as a sop to the masses and wishes to tear it down and destroy his people’s complacency, thinking this will free them once and for all. But religion fosters community and Copeland’s embrace of Marxism is also a tragic embrace of further atomisation for his people, though I doubt McCullers had any sense of this at the time. In fact, given her treatment of family and community throughout the novel, it is possible she would have seen this as a good thing.

Sometimes everything a novel stands for (or against) is revealed in a single passage and so now I take a look at what would, a year ago, have been the concluding paragraph of this review, which I have copied for posterity:

*I would like to conclude this review by drawing attention to an easily overlooked paragraph, part of a conversation Mick has with Harry Minowitz, a minor character serving as the “boy next door” in Mick’s miserable flat-lined America. Harry says: “I used to be a Fascist. I used to think I was. It was this way. You know all the pictures of the people our age in Europe marching and singing song and keeping step together. I used to think that was wonderful. All of them pledged to each other and with one leader. All of them with the same ideals and marching in step together. I didn’t worry much about what was happening to the Jewish minorities because I didn’t want to think about it. And because at the time I didn’t want to think like I was Jewish. You see, I didn’t know. I just looked at the pictures and read what it said underneath and didn’t understand. I never knew what an awful thing it was. I thought I was a Fascist. Of course later on I found out different.” In a novel so focused on the pain of loneliness it is interesting to see McCullers take a brief peek at the wider world and seem to conclude “there are far worse things than loneliness out there.”*

At the time of reading The Heart is a Lonely Hunter I accepted this without much thought. Moral isolation has a price but perhaps it is not always too high to pay. It’s a reasonable supposition. However, in this context it posits a world in which community has no place, where community fosters oppression and must be rejected – as it is throughout this book. Mick’s newfound responsibility is portrayed in a wholly negative light. Blount and Singer are adrift in the world. Dr. Copeland treats his family like fools even as they take him in and getting brought from his empty house to live with them is seen as the climactic failure of his entire life. For forty years his mission was his life and his life was his mission. And yet all remained to be done and nothing was completed. Says Grandpapa: “Yes, I glad to have you. I believe in all kinfolks sticking together – blood kin and marriage kin. I believe in us all struggling along and helping each other out, and some day us will have a reward in the Beyond.”

“Pshaw!” Dr. Copeland said bitterly. “I believe in justice now.”

As a doctor and father of four he’s the most successful person in the entire book (despite being a black man in the South) and none of it means anything to him. But hey, it’s better than fascism!

The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is a work of near-total despair. When you look at McCullers’ life you can see it writ large. In addition to her health and career troubles her marriage to James Reeves McCullers, Jr., was a complete disaster, both of them struggling with bisexuality, alcohol abuse and bouts of suicidal depression. They divorced, remarried and ended the second time with an attempted suicide pact from which Carson McCullers fled. Her husband did not.

Now compare her life with that of another invalid female writer: Anna Sewell. Sewell (1820-1878) sustained a severe ankle injury as a child that left her on a crutch for the rest of her life. Her health deteriorated throughout her adult life and she ended up having to dictate Black Beauty to her mother while dying of hepatitis. She was from a religious family and together with them spent her life doing good works, from establishing a working men’s club to campaigning for causes like abolition and temperance. She was compelled to write Black Beauty to raise awareness and promote humane treatment of the horses which were her chief means of transportation. Or look at the life of Flannery O’Connor (1925-1964) who was sustained in the grip of lupus by her strong Catholic faith, a faith which informed every story she wrote. Why wouldn’t McCullers’ writing be equally informed by her beliefs?

You might say these are unfair comparisons and indeed many of McCullers’ advocates latch onto her sexual identity, absolving her through the victimization that comes with being on the LGBTQ spectrum. Her individual self-destruction, including her disastrous repeat marriage, was thus imposed on her by the larger society. And then we see the New Yorker describe McCullers’ parents thus: “Unlike their neighbors, the Smiths weren’t very interested in religion, and promoted social awareness instead—a Yankee sensibility that was at odds with the town’s conservatism.” So here’s the thing that no one talks about. What sustains a person when he or she draws the short straw? Faith doesn’t have to be Christian to be a weapon against despair but it’s clear to anyone reading about the life of Carson McCullers that she made a tragic situation worse by her own decisions. She wasn’t the only woman writer with a hard and short life: O’Connor, Sewell, the Bronte sisters and Elizabeth Barrett Browning had something powerful, a personal conviction that is reflected in their writing and that clearly gave them strength in a hopeless situation of ever worsening health.

Of course McCullers had personal convictions of her own and these, including social awareness, are on full display in her writings yet what good is a belief system that does not support its own believer? Where is its value? Her novels and stories package despair, full stop. Life as she depicts it is bereft of love or communication and in her later Ballad of the Sad Cafe she expressly stated her belief that humans do not at heart wish to be loved and in fact can only find it oppressive. She did not voice this sentiment through a character; instead she interrupted the entire plot to make this blanket statement. That was her belief system and that was her life. And so she became a darling on the literary scene and now The Heart is a Lonely Hunter is held up as one of the greatest novels of the 20th century when all it really does is diagnose one its greatest pathologies: the death of community.

On the face of it, this is gonna be a short review. The Big Sleep (1939) is Raymond Chandler’s first Philip Marlowe novel, an acknowledged classic of the crime genre, eminently quotable and fun, though a bit lacking in the “subtext” game. Basically, corruption is corrupting. This seminar is over, let’s go talk about the green light on the dock in Gatsby instead.

On the face of it, this is gonna be a short review. The Big Sleep (1939) is Raymond Chandler’s first Philip Marlowe novel, an acknowledged classic of the crime genre, eminently quotable and fun, though a bit lacking in the “subtext” game. Basically, corruption is corrupting. This seminar is over, let’s go talk about the green light on the dock in Gatsby instead.

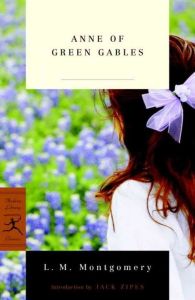

For Anne to take things calmly would have been to change her nature. All “spirit and fire and dew,” as she was, the pleasures and pains of life came to her with trebled intensity. Marilla felt this and was vaguely troubled over it, realizing that the ups and downs of existence would probably bear hardly on this impulsive soul and not sufficiently understanding that the equally great capacity for delight might more than compensate.

For Anne to take things calmly would have been to change her nature. All “spirit and fire and dew,” as she was, the pleasures and pains of life came to her with trebled intensity. Marilla felt this and was vaguely troubled over it, realizing that the ups and downs of existence would probably bear hardly on this impulsive soul and not sufficiently understanding that the equally great capacity for delight might more than compensate.

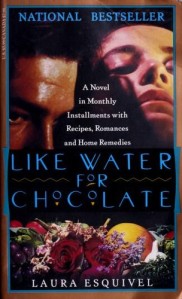

Anyone who thinks Wuthering Heights wasn’t romantic really needs to read Like Water for Chocolate: A Novel in Monthly Installments with Recipes, Romances and Home Remedies, one of those novels whose marketing far eclipses its content. It’s got a quirky subtitle, it promises food, magic, love and female empowerment; it’s short and easy to read, and is written by a Mexican woman, giving it that patina of worldly sophistication that every so often inspires a translated mega-hit in the United States. It’s easy to see how this novel from 1989 was such a smash, with a translation by Carol and Thomas Christensen and a movie both arriving in 1992.

Anyone who thinks Wuthering Heights wasn’t romantic really needs to read Like Water for Chocolate: A Novel in Monthly Installments with Recipes, Romances and Home Remedies, one of those novels whose marketing far eclipses its content. It’s got a quirky subtitle, it promises food, magic, love and female empowerment; it’s short and easy to read, and is written by a Mexican woman, giving it that patina of worldly sophistication that every so often inspires a translated mega-hit in the United States. It’s easy to see how this novel from 1989 was such a smash, with a translation by Carol and Thomas Christensen and a movie both arriving in 1992.

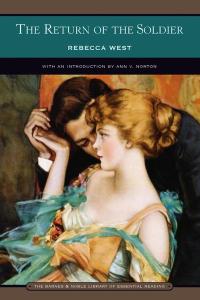

A slim novel from 1918, The Return of the Soldier is the first work of fiction by Dame Rebecca West, the most celebrated woman writer of her day who now drifts semi-forgotten in the shadow of Virginia Woolf. She was too great a contrarian, too independent a thinker for our politicized era and in consequence she is rarely read or talked about anymore. She was the first woman to write a novel about the First World War (for comparison, even Vera Brittain’s famous memoir Testament of Youth came out in 1933, while Woolf’s novel Jacob’s Room was published in 1922, since Woolf only wrote about the Edwardians while the war was on). The premise is really quite simple: Chris Baldry returns from the Western Front shell-shocked and unable to remember the last fifteen years of his life, including his marriage to the beautiful Kitty. He believes he is still twenty and in love with an innkeeper’s daughter called Margaret. Kitty and Jenny, Chris’s unmarried cousin, have to endure the pain of being forgotten by this man whom they adored, while wondering what will bring him back to the present.

A slim novel from 1918, The Return of the Soldier is the first work of fiction by Dame Rebecca West, the most celebrated woman writer of her day who now drifts semi-forgotten in the shadow of Virginia Woolf. She was too great a contrarian, too independent a thinker for our politicized era and in consequence she is rarely read or talked about anymore. She was the first woman to write a novel about the First World War (for comparison, even Vera Brittain’s famous memoir Testament of Youth came out in 1933, while Woolf’s novel Jacob’s Room was published in 1922, since Woolf only wrote about the Edwardians while the war was on). The premise is really quite simple: Chris Baldry returns from the Western Front shell-shocked and unable to remember the last fifteen years of his life, including his marriage to the beautiful Kitty. He believes he is still twenty and in love with an innkeeper’s daughter called Margaret. Kitty and Jenny, Chris’s unmarried cousin, have to endure the pain of being forgotten by this man whom they adored, while wondering what will bring him back to the present.

The complete text of

The complete text of

conducted by Thomas Schippers (1930-1977) at the Grand Theatre de Geneve, 1963. Regina Resnik as Carmen, Mario Del Monaco as Don José, Tom Krause as the toreador Escamillo and Joan Sutherland as Michaela (not her most memorable role). Schippers had a keen sense of performance and could summon the maximum level of energy from his orchestra at breakneck tempos without sacrificing clarity, capturing the irrepressible joy inherent to the opera (and which Nietzsche commented on) without losing the menace that underlies it. He presented Carmen as something exciting and alive, not a museum piece. His rendition makes the opera immediate again, without resorting to casting gimmickry or modernism, relying on passion, on love. We can only regret his untimely death, with so many performances still ahead of the man.

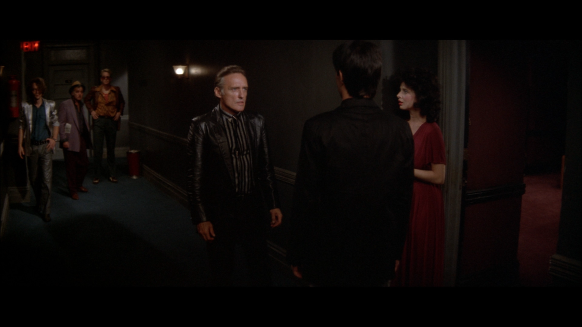

conducted by Thomas Schippers (1930-1977) at the Grand Theatre de Geneve, 1963. Regina Resnik as Carmen, Mario Del Monaco as Don José, Tom Krause as the toreador Escamillo and Joan Sutherland as Michaela (not her most memorable role). Schippers had a keen sense of performance and could summon the maximum level of energy from his orchestra at breakneck tempos without sacrificing clarity, capturing the irrepressible joy inherent to the opera (and which Nietzsche commented on) without losing the menace that underlies it. He presented Carmen as something exciting and alive, not a museum piece. His rendition makes the opera immediate again, without resorting to casting gimmickry or modernism, relying on passion, on love. We can only regret his untimely death, with so many performances still ahead of the man. production of Carmen, performed by the Compania Antonio Gades. Gades (1936-2004) was responsible in the late seventies for the creation of the Spanish National Ballet. His choreography eliminated the signs of tourism and sterility from flamenco, saying in 1984 about his newly created Carmen: “Our dance has strength, it has real life. It is not an academic dance, where what is shown is virtually a study, a technique, some forms… But rather our dance is a vital thing; it is the dance of culture, through which the soul of an entire people is expressed.”

production of Carmen, performed by the Compania Antonio Gades. Gades (1936-2004) was responsible in the late seventies for the creation of the Spanish National Ballet. His choreography eliminated the signs of tourism and sterility from flamenco, saying in 1984 about his newly created Carmen: “Our dance has strength, it has real life. It is not an academic dance, where what is shown is virtually a study, a technique, some forms… But rather our dance is a vital thing; it is the dance of culture, through which the soul of an entire people is expressed.”